ew aircraft are as instantly recognizable—or as controversial—as the V-22 Osprey. With its tiltrotor design, the Osprey combines the vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) abilities of a helicopter with the speed and range of a fixed-wing airplane. On paper, its performance is impressive:

- Range: 1,627 km (over 1,000 miles)

- Payload capacity: 9,072 kg

- Top speed: 316 mph (508 km/h)

These capabilities make the Osprey one of the most ambitious aerospace projects ever fielded. But behind its striking silhouette lies a story of engineering brilliance, costly compromises, and potential opportunities for reinvention.

Origins in Crisis

The V-22 was born out of failure. In 1980, the U.S. military’s Operation Eagle Claw—a mission to rescue hostages in Tehran—collapsed due to a lack of aircraft capable of long-range infiltration and vertical extraction. The Osprey was developed as the solution: a machine able to fly far and fast, yet land in confined spaces.

In that sense, it delivered. No other platform before it had bridged the gap between helicopters and airplanes so effectively.

Engineering Marvel, Operational Challenge

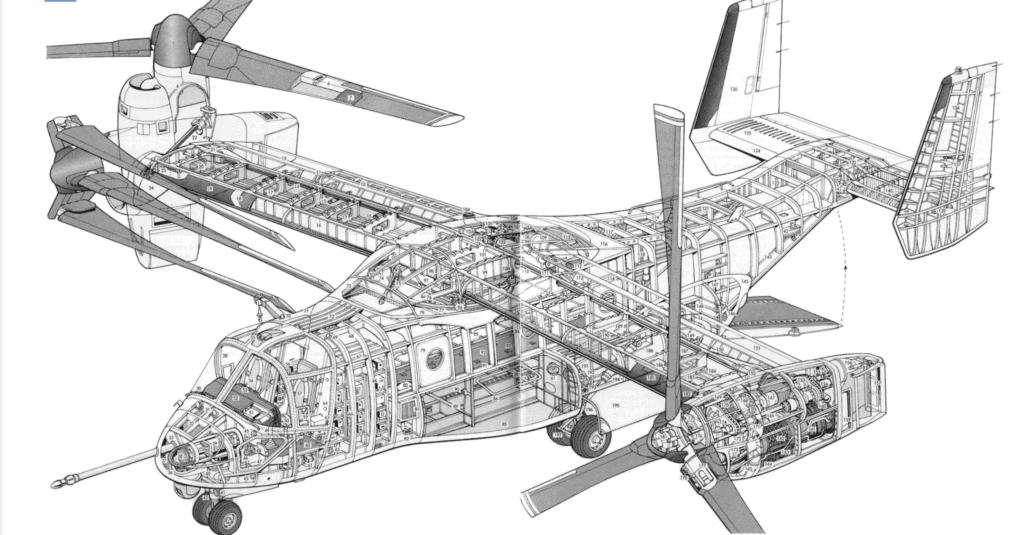

The Osprey’s capabilities come at a price. Its tiltrotor system is among the most complex propulsion architectures ever fielded. The aircraft requires:

- Five heavy gearboxes (including two proprotor units, a mid-wing gearbox, and tilt-axis gearboxes).

- A 38:1 gear reduction system to convert turboshaft output into rotor torque.

- An interconnect drive shaft weighing ~1,700 kg to allow one engine to power both rotors.

- Dual redundant hydraulics to tilt the massive nacelles.

This complexity has contributed to both mishaps and persistently high operating costs—around $24,000 per flight hour. By comparison, the Osprey is heavier than the CH-47 Chinook yet carries less payload (9.1 vs. 12.6 tonnes), underscoring the compromises inherent in its design.

The Weight Spiral

At the heart of these compromises lies a vicious cycle:

- Large rotors demand heavy wing structures.

- Stronger wings require more powerful engines.

- Bigger engines add even more weight.

The result is a machine burdened by its own ingenuity—an engineering marvel, but one that pays for its performance with efficiency and maintainability.

Enter Electrification

What if that cycle could be inverted? Advances in electric propulsion suggest a path forward—not through batteries alone, which lack sufficient energy density, but via hybrid-electric systems.

- Motors with high power-to-weight: Wright Electric, for example, has demonstrated a 2.5 MW motor weighing only 150 kg. Replacing each 440 kg turboshaft engine with pairs of such motors could save weight exactly where it matters most—the wingtips.

- Simplified architecture: Electric motors eliminate the need for complex gearboxes and interconnect shafts. Electrical controllers (solid-state hardware with no moving parts) can directly manage rotor torque and speed.

- Lighter tilt mechanisms: A 150-kg nacelle is far easier to actuate than a 440-kg one, enabling the use of electromechanical actuators instead of heavy hydraulic systems.

The Hybrid Tradeoff

Electrification is not free. A hybrid system would require:

- A 5 MW turbogenerator, weighing 1–1.5 tonnes.

- Inverters, cabling, and ~200 kg of batteries for power management.

This adds back ~1.7 tonnes, but crucially, the mass shifts from the wing tips to the fuselage, where it can be supported more efficiently. At the same time, eliminating hydraulic systems and drive shafts could yield a net reduction in both weight and complexity.

Rethinking the Osprey

The V-22 Osprey remains an icon of aerospace ambition: a machine that answered a mission need but has been dogged by its costs and complexity ever since. Through electrification, however, there may be an opportunity not just to replace engines, but to reimagine its architecture—breaking the cycle of weight and compromise that has defined it for decades.

Electrification could transform the Osprey from a marvel weighed down by its own ingenuity into a platform that fully realizes its potential.

V-22 Osprey: Current vs. Hybrid-Electric Concept (Approximate Weights)

| Subsystem | Current V-22 (Baseline) | Hybrid-Electric Concept | Δ Weight & Notes |

| Engines / Propulsion Units | 2 × Rolls-Royce AE1107C turboshafts, 440 kg each → 880 kg | 4 × 2.5 MW electric motors, 150 kg each → 600 kg | –280 kg, weight removed at wing tips (critical for wing loading & stiffness) |

| Proprotor Drive System (gearboxes, interconnect shaft, tilt gearboxes) | 1,714 kg | Eliminated | –1,714 kg |

| Tilt Actuation | Dual redundant hydraulic system, ~300–400 kg | Electromechanical actuators (similar to eVTOL), ~100–150 kg | –200 to –250 kg |

| Turbogenerator (hybrid power source) | Not applicable (engines provide shaft power directly) | 5 MW turbogenerator, 4–5 kW/kg → 1,000–1,500 kg | +1,000–1,500 kg (but weight centralized in fuselage, not wingtips) |

| Power Electronics (inverters, rectifiers, cabling) | Minimal (hydraulic & mechanical transmission dominant) | ~300–500 kg (SiC-based at ~20 kW/kg) | +300–500 kg |

| Batteries / Energy Buffer | None (fuel only) | Buffer pack for transients, ~200 kg | +200 kg |

| Infrared Suppression System | ~150–200 kg | Retained (no change) | 0 |

| Wing Structural Reinforcement | Heavy reinforcement required due to engines + gearbox mass at tips | Lighter reinforcement possible (less torque, lighter nacelles) | –200 to –400 kg (estimate) |

Totals

- Current V-22: ~3,094 kg (engines + drive system + hydraulics, excluding structure/fuel).

- Hybrid Concept: ~2,200–2,950 kg (motors + turbogenerator + electronics + lighter tilt/wing).

Net Effect: Roughly 150–900 kg lighter overall, with the added benefit of shifting weight inboard (from wingtips to fuselage). This improves structural efficiency, reduces torque on the wings, and lowers maintenance complexity by eliminating the most failure-prone components (gearboxes, shafts, hydraulics).